The Reason

In middle school, I wasn’t athletic by any rendition of the word: I averaged about a twenty-one-minute mile, couldn’t lift my own body weight, and would have been lucky if I managed a handful of knee push-ups during physical fitness testing in gym class. Despite my lack of strength or stamina, I always loved the idea of dodgeball—it was the first time in gym class where I felt my mind could outperform my physical capabilities with strategy, tactic, and a little bit of whit.

The gymnasium felt more like a battle arena. Encircling the entire basketball court were thick steps of gray concrete, about three feet high and three feet deep. There were four or five of these massive steps that served as seats during official basketball games—from the top row you could touch the ceiling of the gym and look down into the pit the steps created. On the outside walls, only accessible from the top row of seats, were long windows that opened outwards. The only way into the arena was through a long, antiquated hallway that eventually opened directly onto the court.

The day started like any other—picked last by default and stuck wearing a red breathable sleeveless jersey that’s two sizes too small. The rules are standard team dodgeball: struck players sit in order of being hit, caught balls allow for teammates to come back into the game, and for games that went on too long, the teacher could call “red line” allowing the teams to get closer before firing. As the whistle blows, in typical fashion, I stand on the baseline, right under the basketball hoop. I watch as my more ambitious teammates charge the front line—some instantly striking our opponent, others instantly being struck. I’m content here for now.

In what seems like the blink of an eye, I’m left alone as the only member of the red team. As I stare at three of the most athletic, agile kids in our class, my teammates cheer me on by yelling random bits of strategy. They still believe in me. Can I actually win? I’m sure the blue team left me for last because I would be the easiest to hit. Why does my team have so much confidence in me? They’ve seen me do push-ups. They lapped me four times during our warmup run. Now they believe in me?

Lost in my own thoughts, a big orange ball rolls right towards me—easy for blocking. Maybe I can at least delay the game…get them tired for the next round. I pick it up, and before I realize what I’m doing, I hurl it at their weakest player. It glazes his ankle. My teammates erupt on the bench. They do believe in me. I think I can do this. Two on one now.

I back up to the baseline again and find a small ball to defend myself—it’s one of those rubbery, dense balls, not ideal for blocking, but the one I really need is twenty feet to my right. No chance I make it there. My opponents huddle up and whisper, plotting no doubt. What’s taking them so long? They both have two balls in hand. Just throw them already. My ankle hurts…and I definitely shouldn’t have had that pizza for lunch. Just as they start advancing, the teacher yells, “red line!” That felt planned. Surely my team now knows that I have no chance here. But then why are they getting louder?

My opponents advance and now have me backed into the corner. They look so determined. I gave it a good run—at least my GPA’s still higher than theirs. In a moment of haste, one decides to strike—it’s a ball coming straight for my chest. It’s one of those soft, squishy balls—not a practical artillery choice for the winning strike. I try to block it but instead it lands directly into my arms. The bench erupts again and one of my teammates rushes back into the game. I toss her the ball that I just caught, and without hesitation, we rush the remaining player—I go low, she goes high. We both make contact, and in an instant, we are swarmed by our teammates.

Those of you who are connected with me on social may have heard this story before…but what you don’t know is what happened during the subsequent games: struck easily, first, and hard, without the possibility of touching another ball for the rest of the block—back to normal.

Do you see the connection to Net Promoter Score (NPS) yet?

Keep reading.

The Rant

If you were to have asked my teammates at the very moment they stormed the court, with the adrenaline pumping, having just witnessed the greatest comeback in middle school dodgeball history, “how likely are you to recommend Justin to a friend or colleague?” it would have been a historic promoter fest—10s all around, the perfect NPS, and all champions and advocates for me. Compare that to the score if the same question was asked before, during, or after the last game of the day, with disappointing glares and gazes of disbelief—I’d have some remediating to do.

Think about the scenarios and timing when you choose to ask your customers this question. Think about what the expected versus actual customer experience is at the point in the journey when you’re collecting NPS responses.

Let’s dive into a few scenarios—

1.Collecting NPS as part of a support survey

I see it all the time in my personal subscriptions—I submit a ticket or contact support for a specific issue and once the issue is resolved, I get the email almost immediately asking how likely I am to recommend their product to a friend. The majority of the time, my response is going to be based on my satisfaction with the support team (Customer Satisfaction or CSAT), how easy the process was (Customer Effort Score or CES), how long I had to wait for someone to respond (First Response Time or FRT), and if my issue was actually resolved in that interaction (First Call Resolution Rate or FCRR). Read that last sentence again—how many times was the product mentioned? That’s right, zero. This scenario collects NPS in moments where other CX metrics are the driving factors for the response—not a very telling reflection of advocacy. NPS is already the biggest lagging indicator many CS organizations choose to focus on, but by collecting it as part of a support survey, we are making it even more reactive—the lagging-est laggard of indicators.

2. Collecting NPS during onboarding

The key word here is “during.” Why anyone would intentionally choose to ask a customer if they are willing to recommend their product, likely before any value is received, any data connected, or feet are metaphorically wet in the product, is beyond my comprehension. Are we doing this in hopes of the pomp and flash from the days of pre-sale and demos still being fresh in the customer’s mind? That the promises of functionality and features we’ve made will be enough for the customer to report as a promoter? So that we can flash our ridiculously high NPS to the industry for a proverbial pat on the back? Again, think about your personal subscriptions here. You subscribe to a new service and within a day or two, before you’ve had time to fully dive into content or functionality, you get asked if you like the service enough to recommend it to someone else. How are you supposed to know? You only just subscribed. At best, you’re giving your response based on first reaction and again…first reaction is not a good reflection of long-term advocacy. (For the record, I’m totally fine with collection of NPS post-onboarding. There are at least some rationalizations to make for that scenario and tracking that can be done to see how it changes over time, and how certain variables can impact NPS—a solid baseline NPS for a customer seems rational and that can only be truly and accurately captured after onboarding is complete.)

3. Collecting NPS at the time of churn

This one seems obvious…but believe it or not, it happens. I’m all for a post-churn survey to understand your customer’s reasoning behind leaving your service or product offerings behind; collecting feedback from churned customers can help us better understand and identify churn risk factors and how they relate to other variables in our customer’s experience—we need to understand why they’re leaving and what led to that decision. With that information at our disposal, we can establish and iterate on thorough risk management plans to mitigate churn based on those leading indicators. I acknowledge that sometimes the reason for churn is summed up to money, a lack of control or budget, or even turnover among stakeholders—but none of those reasons are justification for using NPS in this scenario. Let’s imagine for a moment that we diligently collect NPS at the time of churn, and the majority of customers report as detractors or passives. The action that would turn these detractors to promoters at the point of churn wouldn’t come from your NPS motions to remediate—they would be part of your overall risk management plan. And even in the scenario where you identify promoters based on exit NPS, what are you going to do with that data? Do you want advocates and champions promoting your product or service who don’t even use your product or service? It’s not a very strong testimonial if it’s coming from someone who found a reason to take their business elsewhere.

4. Collecting NPS intentionally at customer high points

If you have an automated NPS survey set up based on a customer meeting a specific positive milestone, like Time to First Value (TTFV or TTV), you are intentionally skewing your NPS scores; other than puffing up our numbers and serving our own bias, there is no value that your customer is receiving by collecting NPS in these scenarios. If the goal of NPS is to help identify advocates and champions of your brand (which it is), and you are only measuring NPS when the customer has a positive experience, you aren’t collecting a score that adequately captures their complete view of your product or service. You are capturing their sentiment based on their current condition, which could be more likely to fade if it is only capturing the emotional response based on the specific positive milestone. Think about these two scenarios: “Sweet, I’ve got all my data connected. Yes, I recommend your product!” versus “Oh, I didn’t realize it couldn’t do that. How am I going to make this work?” You are essentially asking my teammates how likely they are to recommend me based on my one fantastic game of dodgeball—the first game of the day versus the last.

5. Collecting NPS for customer health scores

This one is going to be controversial but hear me out. Let’s think about it logically for a second: we all agree that NPS is generally a lagging indicator—it’s reported after an event or usage of our product or service, that then impacts the likeliness to recommend that product or service. We know NPS is a very reactive motion, from sending the survey to potentially actioning or remediating well after the event of causation. So, why would we want NPS scores in a customer health model that is intended to be proactive and identify risk factors that indicate customer’s not receiving full value from your product before they become a churn risk? It’s in our nature to look to the past to plan for the future, but very rarely do I see NPS planned and executed on to the point where it can act as a leading indicator, even a little bit—it just doesn’t work. And if we assume scenarios one through four are happening every day in the industry (and they are), we know that we are already skewing our NPS anyway. Why should we compromise our forward-looking customer health scores and lessen the impact they can have on our CSMs’ ability to help customers receive value from our products? Just because you have the data available doesn’t mean it should be thrown into your health score. Run the model to see the impact and accuracy without NPS. You might be surprised. (If this section leaves you wanting more, don’t worry. There will be a future rant specific to health score, but for now I recommend checking out this Customer Success Unlocked webinar from last month with David Sakamoto and Neal McCoy on the topic.)

The Resolution

This rant could go on for weeks if I attempted to thoroughly publish a prescription methodology for effective NPS.

Instead, I want to end this week with my simple, but effective recommendations that you can implement in your NPS model and methodology today to make it more effective and beneficial to your customers.

Stop thinking about NPS as a metric

The purpose of NPS is to help identify advocates of your brand—to target champions who receive value from your product or service to spread awareness, ideally in the form of testimonials, to companies who fit your ideal customer profile—becoming intentional and strategic in our implementation and execution of NPS. Viewing NPS as another CX metric to track muddies the potential impact it can have on your organization. View NPS as a means to identify advocates and champions of your brand—nothing more.

Remediate, Remediate, Remediate

While the purpose of NPS is to identify those advocates of the brand, you will have detractors—if you don’t, you’re doing it wrong. Keeping the philosophy of brand advocacy front and center, view those detractors as potential promoters. Establish a process to reach out and remediate immediately after the response is received. If you are allowing for comments to be submitted with NPS, read them! It shouldn’t have to be said, but there is so much insight in our qualitative data that CS Analysts can analyze to highlight commonly overlooked gaps in process, product functionality, or service effectiveness. Remediate and track progress. Can your organization show the percentage of detractors turned promoters, and how that has impacted revenue generated from, and by, those critics turned advocates based on your remediation process? Probably not. (No scalability arguments are allowed here. There are ways to remediate using automation or tech-touch as a foundation.)

Timing, Bias, and Deployment

There is no universal answer here, but there are things we can all consider. Before establishing the process for which NPS will be collected—including the how, when, and why—evaluate what’s going on in the customer’s experience at the point in their journey when you plan to utilize NPS. Try to eliminate any bias that may be influencing the timing and results of your NPS results. Establish an NPS deployment methodology that makes sense for your business but isn’t reliant on especially positive customer experiences or experiences where the customer has had to react to any positive or negative scenario. Eliminating all bias might not be possible, but setting criteria for NPS deployment time, like once a month or once a quarter (if the business model supports that timing) will help keep NPS relative to the customer journey. When you decide the timing and do your due diligence to mitigate bias, deploy the NPS survey with two questions maximum: one asking how likely they are to recommend your product or service to a friend or colleague, and an optional place for them to provide qualitative data to justify their response. Don’t muddy up the NPS survey. Keep it simple, straightforward, and focused.

Advocates and Champions

Do you have a process to reach out to promoters to capitalize on their advocacy, as indicated by the NPS results? How many champions of your brand aren’t being contacted? My guess is that you have customers today who would be willing to serve as references, provide written or video testimonials, or even serve on a Customer Advisory Board (CAB) because they believe in your products and accompanying services. So, why is no one asking them? You’re collecting their feedback and recording their nines and tens, maybe even entering them in a variety of your systems, reporting their high advocacy…but no one is actually asking the questions that require them to take action on those sentiments to represent and promote your brand in the marketplace—close the loop, easy wins, ripe for the taking.

Utilize the Matrix

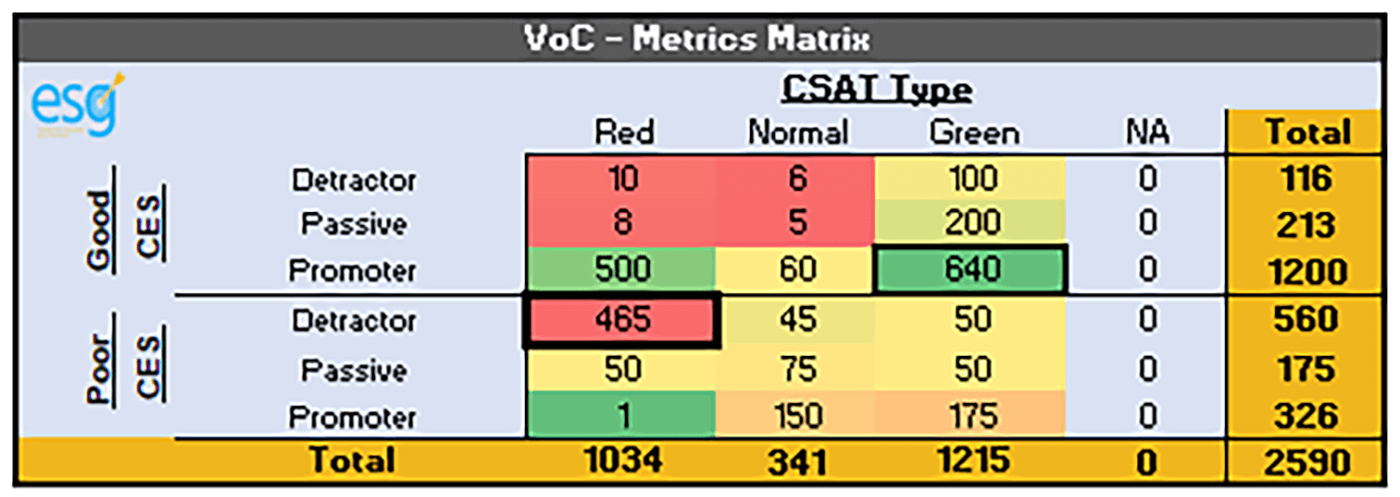

If you insist on looking at NPS to assess the health of your customers, at least look at multiple variables to highlight the customers that are truly at risk. The visual below is a very simple matrix to categorize your customers by three variables: Customer Satisfaction (CSAT), Customer Effort Score (CES), and Net Promoter Score (NPS). This can also help with scalability—instead of starting with remediating all detractors, start with poor CES, red CSAT, detractors. Likewise, using this methodology gives you a target set of customers (good CES, green CSAT, and promoters) who are ideal to target for advocacy motions—satisfied and all-around happy customers. The variables should make sense for your business. Just make sure it gives you a focused approach to remediation and holistically assesses your customers.

My one great game of dodgeball in middle school didn’t change the fact that I continued to be picked last—even in a college gym class, my reputation preceded me. I was a one-hit-wonder, a sequence of luck and convenient timing, a two living a transient life of a ten, and when time passed and the circumstance of the scenario was realized—that the advocacy exhibited for me was misplaced, the time for remediation had passed, and my brand was fatigued, leaving me with a severe case of scenario-based NPS. Don’t be like me. Don’t fool yourself or your brand by collecting NPS at times of high fives and applause. Those tens are actually twos. Until next week.

Missed last week’s installment of Rants of a Customer Success Analyst? Go back and read! And keep an eye out for the next Reason, Rant, and Resolution next week.